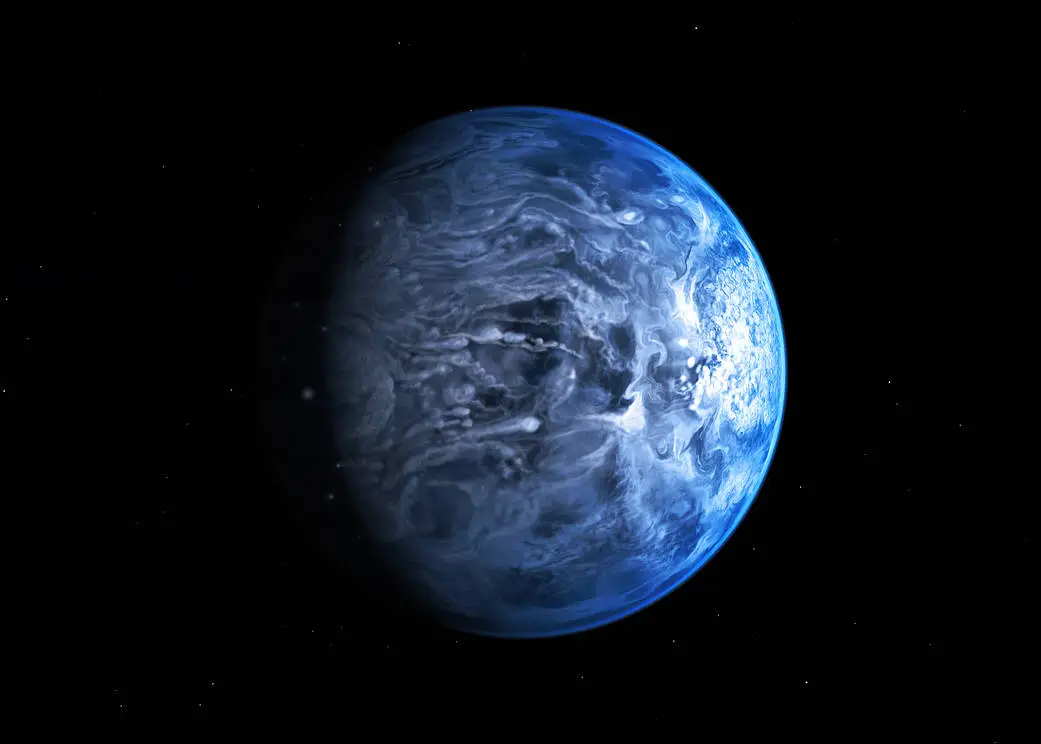

Scientists have discovered hydrogen sulfide, a gas that smells like rotten eggs, in the atmosphere of a Jupiter-like exoplanet named HD 189733b. This finding sheds light on the extreme conditions of this distant world and enhances our understanding of exoplanetary atmospheres. HD 189733b, discovered in 2005, is located 64 light-years away in the constellation Vulpecula. This exoplanet, which exists outside our solar system, is about 10 percent larger than Jupiter in diameter and mass…….Continue reading….

By: Hilary Ong

Source: DMR News

.

Critics:

At higher altitudes, where air drag is less significant, orbital decay takes longer. Slight atmospheric drag, lunar perturbations, Earth’s gravity perturbations, solar wind, and solar radiation pressure can gradually bring debris down to lower altitudes (where it decays), but at very high altitudes this may take centuries. Although high-altitude orbits are less commonly used than LEO and the onset of the problem is slower, the numbers progress toward the critical threshold more quickly.

Many communications satellites are in geostationary orbits (GEO), clustering over specific targets and sharing the same orbital path. Although velocities are low between GEO objects, when a satellite becomes derelict (such as Telstar 401) it assumes a geosynchronous orbit; its orbital inclination increases about 0.8° and its speed increases about 160 km/h (99 mph) per year. Impact velocity peaks at about 1.5 km/s (0.93 mi/s).

Orbital perturbations cause longitude drift of the inoperable spacecraft and precession of the orbital plane. Close approaches (within 50 meters) are estimated at one per year. The collision debris pose less short-term risk than from a LEO collision, but the satellite would likely become inoperable. Large objects, such as solar-power satellites, are especially vulnerable to collisions.

Although the ITU now requires proof a satellite can be moved out of its orbital slot at the end of its lifespan, studies suggest this is insufficient.[61] Since GEO orbit is too distant to accurately measure objects under 1 m (3 ft 3 in), the nature of the problem is not well known. Satellites could be moved to empty spots in GEO, requiring less maneuvering and making it easier to predict future motion.

Satellites or boosters in other orbits, especially stranded in geostationary transfer orbit, are an additional concern due to their typically high crossing velocity. Despite efforts to reduce risk, spacecraft collisions have occurred. The European Space Agency telecom satellite Olympus-1 was struck by a meteoroid on 11 August 1993 and eventually moved to a graveyard orbit. On 29 March 2006, the Russian Express-AM11 communications satellite was struck by an unknown object and rendered inoperable; its engineers had enough contact time with the satellite to send it into a graveyard orbit.

In 1958, the United States of America launched Vanguard I into a medium Earth orbit (MEO). As of October 2009, it, the upper stage of Vanguard 1’s launch rocket and associated piece of debris, are the oldest surviving artificial space objects still in orbit and are expected to be until after the year 2250. As of May 2022, the Union of Concerned Scientists listed 5,465 operational satellites from a known population of 27,000 pieces of orbital debris tracked by NORAD.

Occasionally satellites are left in orbit when they’re no longer useful. Many countries require that satellites go through passivation at the end of their life. The satellites are then either boosted into a higher, “graveyard” orbit or a lower, short-term orbit. Nonetheless, satellites that have been properly moved to a higher orbit have an eight-percent probability of puncture and coolant release over a 50-year period. The coolant freezes into droplets of solid sodium-potassium alloy, creating more debris.

Despite the use of passivation, or prior to its standardization, many satellites and rocket bodies have exploded or broken apart on orbit. In February 2015, for example, the USAF Defense Meteorological Satellite Program Flight 13 (DMSP-F13) exploded on orbit, creating at least 149 debris objects, which were expected to remain in orbit for decades. Later that same year, NOAA-16 which had been decommissioned after an anomaly in June 2014, broke apart on orbit into at least 275 pieces.

For older programs, such as the Soviet-era Meteor 2 and Kosmos satellites, design flaws resulted in numerous break-ups – at least 68 by 1994 – following decommissioning, resulting in more debris. In addition to the accidental creation of debris, some has been made intentionally through the deliberate destruction of satellites. This has been done as a test of anti-satellite or anti-ballistic missile technology, or to prevent a sensitive satellite from being examined by a foreign power.

The United States has conducted over 30 anti-satellite weapons tests (ASATs), the Soviet Union/Russia has performed at least 27, China has performed 10 and India has performed at least one. The most recent ASATs were the Chinese interception of FY-1C, Russian trials of its PL-19 Nudol, the American interception of USA-193 and India’s interception of an unstated live satellite.

Space debris includes a glove lost by astronaut Ed White on the first American space-walk (EVA), a camera lost by Michael Collins near Gemini 10, a thermal blanket lost during STS-88, garbage bags jettisoned by Soviet cosmonauts during Mir’s 15-year life, a wrench, and a toothbrush. Sunita Williams of STS-116 lost a camera during an EVA. During an STS-120 EVA to reinforce a torn solar panel, a pair of pliers was lost, and in an STS-126 EVA, Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper lost a briefcase-sized tool bag.

A variety of approaches have been proposed, studied, or had ground subsystems built to use other spacecraft to remove existing space debris. A consensus of speakers at a meeting in Brussels in October 2012, organized by the Secure World Foundation (a U.S. think tank) and the French International Relations Institute, reported that removal of the largest debris would be required to prevent the risk to spacecraft becoming unacceptable in the foreseeable future (without any addition to the inventory of dead spacecraft in LEO).

To date in 2019, removal costs and legal questions about ownership and the authority to remove defunct satellites have stymied national or international action. Current space law retains ownership of all satellites with their original operators, even debris or spacecraft which are defunct or threaten active missions. Multiple companies made plans in the late 2010s to conduct external removal on their satellites in mid-LEO orbits.

For example, OneWeb planned to use onboard self-removal as “plan A” for satellite deorbiting at the end of life, but if a satellite were unable to remove itself within one year of end of life, OneWeb would implement “plan B” and dispatch a reusable (multi-transport mission) space tug to attach to the satellite at an already built-in capture target via a grappling fixture, to be towed to a lower orbit and released for re-entry.

Chair workouts plan according to your age

Leave a Reply